The Jim Austin Computer Collection

Cadlinc

GC-0041-106

We are actively researching this machine. The evidence points to it being the prototype Sun 1 made by Cadlinc - but its not 100% sure. If it is, it will be a very important machine in the history of computing as Sun Microsystems became a multi-billion dollar company from this machine before being sold to Oracle. It could be the earliest known Sun computer. Donted by Kevan haydon to the collection in sept 2003.

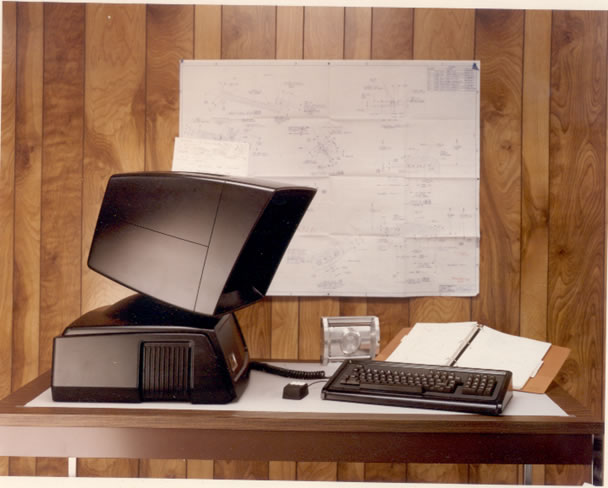

We think it came from the CAD in Cambridge, UK. It may have been sent there for evaluation. Its histiry is being confirmed by Walter R Siekierski ex Cadlinc. Indications that its a Sun 1 prototype is that it has a 3 Mbit Ethernet card, all the Cadlinc systems had 10Mbit, but Sun 1 had a 3Mbit card to start with. The case is more like the Sun 1 than Cadlincs own version of the system shown below left. A Sun 1 is shown on the right (wikimedia). The case of our Cadlinc machine is very like the Sun 1. It has a sticker on it - SN01, this indicates it was the first development machine supplied to organisatiaons for evaluation outside the company. Walter reports earlier machines were developed but never released.

|

|

|---|

The Sun 1 was the first computer made by sun and only 200 were thought to be made.

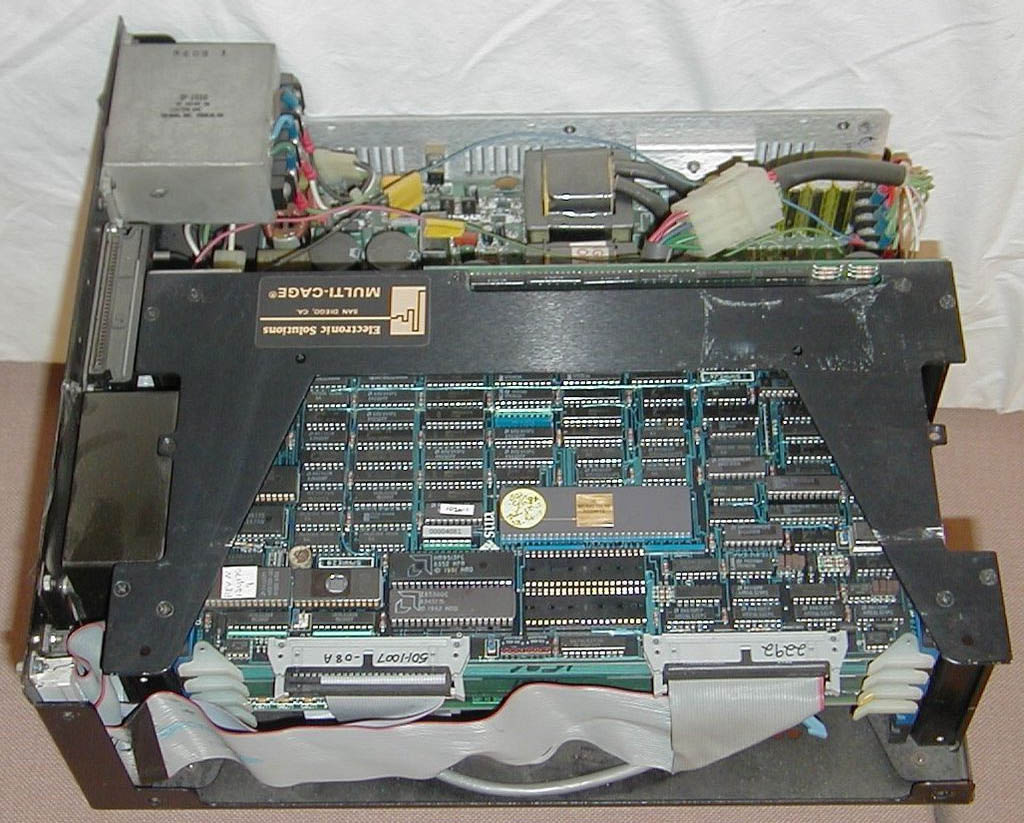

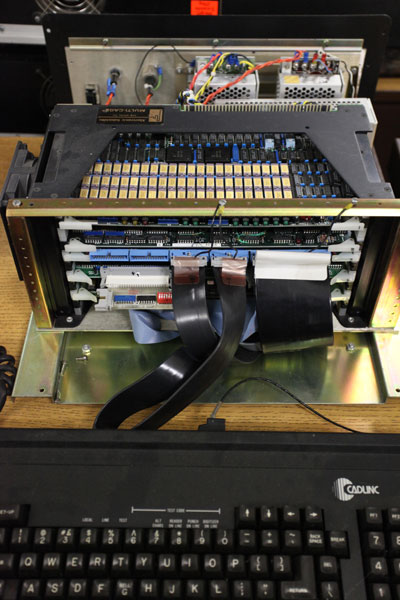

The image below shows a Sun 1 rack - compare this with the pictures of the cadlinc below. The Cadlinc rack is shown with all boards in place.

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

Its serial number - indicating it was number 1. |

Note from MIke Causer, who donated it to

There was an outfit in Detroit who were the USA licencees of GNC from

the CADCentre, called System Associates Inc, run by Doug Werman and

Mike Sterling. When Bricad (British CAD) was founded in Spring Lake

NJ to sell the CADCentre's PDMS its employees were Dick Newell and

Mike Causer. Now Bricad had about half the money it needed to buy

and maintain a computer, a Prime 400, and System Associates whom we

knew well through the CADCentre connection also had about half the

money needed for a P400. So we did the obvious thing, Bricad bought

it, SAI installed it, fed it, maintained it and hooked it up to

Telenet. I then roamed around the USA with an accoustic coupler (an

early form of modem), logging in to "my" machine at 300baud to do

graphics demos! This was 1977 remember, very high tech at the time

:-)

In the very early 1980s Motorola were talking about their new

microprocessor line, the 68000, and lots of people were getting

excited about the possibilities of distributed computing with it.

The chief designer from Prime left and started Apollo to use the

M68000, and there were some in the computer lab at Stanford (Palo

Alto CA), where Andy Becholdstein (sp?), Bill Joy et al. were

playing with them. These guys came up with an all-in-one-box design

they called the S.U.N. for Stanford University Network. Mike

Sterling at SAI was a real hardware man, and wanted to get into the

new micros, and he & Doug sold their business to John West who had

made a lot of money from printers and was looking for something to

invest in. They bought the rights to make the S.U.N. machines and

the payment was that the first 50 or so machines off the production

line would go to Stanford. They set up their factory in Chicago, and

called the new business Cadlinc. (At last I get to the point.)

By this time I had joined Cambridge Interactive Systems, and was

keeping in touch with Cadlinc because CIS also wanted to get into

this new hardware. We had looked at Symbolics and Apollo already,

but wanted a deal with a smaller outfit where we would have more

influence. Because of the talks with Cadlinc Dick (by then a

Director of CIS), knew that they were looking for a chief designer,

and that his brother Martin (ex CADC, PARC, etc) was looking for a

job. So Martin joined Cadlinc at about the same time that

Computervision bought CIS. CV's need for CIS was to tap into what we

were doing in this line, and to buy their major competitor in UK &

Germany. They halted the talks with Cadlinc, and started again on

going round the M68000 users.

Now by this time the guys at Stanford had seen that this was going to

be a good thing and had found $4million in capital to start making

the S.U.N. design for themselves -- called Sun Microsystems of

course. The Sun-1 was a mildly upgraded version of the S.U.N.,

because Cadlinc had been working on development of it too. The very

very early machines were all one box, but it wasn't long before the

need to add other cards led to the deskside jobs with multibus.

There were lots of people making multibus addons by then, ethernet,

floating point, SMD controllers, memory, so it was a good way to go.

Sun were after a general scientific market, heavy graphics users, &

so on. Cadlinc wanted to make systems for a specific market, the

engineering busineses, possibly with NC already in use. so over time

the lower ambitions of Cadlinc meant that their sales didn't take off

in the same way, and Sun boomed. So there was a point at which they

were big enough to have subsidiaries outside the USA, but couldn't

compete with Sun in development or in scale of manufacture. They

realised they couldn't keep up and switched to being software people,

installing their operating system on equipment bought from Sun. CV

of course decided to work with Sun, but signed a deal that got them

manufacturing rights to the Sun-2, but not to developments of it.

That was really dumb, but they'd been making DG Novas under licence

for 10 years and hadn't cottoned on to the pace of development in

this new line.

The last time I came across Cadlinc was 5 or 6 years ago, but I

believe that they are still going, with a base in Nottingham in this

country. I do have some product brochures which may give you an idea

of how their system works, but I suspect that if you have a 68010

system you might be able to bring up SunOs on it too.

NB: this was written an the late 1990s.

Its relationship with Sun 1... from 'http://forum.stanford.edu/carolyn/valley_of_hearts'

Appendix A: The Founding of Sun Microsystems

An electronic mail message from Vaughan Pratt (1994, March 28)

Hi, Carolyn. Here's a quick rundown on events around the 79-83 period. This is all very incomplete and rushed. I have megabytes of old email messages that I've been meaning to go through to remind myself of everything that happened back then, but this is a big project that is likely to remain on the back burner for some time to come.

I'm not sure as to the exact timing of when Forest (Baskett) decided to start the Sun terminal project, but a key event precipitating its progress occurred in late 1979 when Forest and Andy [Bechtolsheim] went to Comdex, where they saw the Nu terminal, MIT's version of the (then-unborn) Sun workstation. Forest knew they could achieve the same performance and functionality in a much smaller and cheaper package, and they went back to Stanford to begin work on a Stanford version of the Nu terminal, to be called the Stanford University Network (SUN) terminal.

The principals I recall from that period were

Staff: John Seamons, Rob Poor, and Jeff Mogul (taking a year's break from being a PhD student here). John Seamons was lured away at the end of summer 1980 by an irresistible offer from newly-formed Lucasfilm. Rob Poor followed him there not too long after.

Students: Andy Bechtolsheim, Bill Nowicki, and Jeff Mogul after his one-year stint on staff. There were other students but these three were easily the most prominent on this project.

I arrived at Stanford in July 1980, on a year's sabbatical from MIT, to start a computer aided verification project with Derek Oppen. The week before I arrived Derek quit Stanford, and I went in search of another group to work with for the duration of my sabbatical. The Sun terminal project was most to my taste, and I joined up and went to work that summer writing software for the hardware that Andy had produced up to that point. In the first month I wrote a trivial window system and a graphics terminal emulator. I used this as my graphics terminal for the rest of that summer, during which I wrote a disassembler for the 68000 and made a start on a microkernel I called Sunix.

At the end of summer Forest went to Xerox PARC on leave from Stanford, from which he never returned. (A couple of years later Forest left PARC to head up DEC's new Western Research Lab. in Palo Alto, sibling to DEC's equally new Systems Research Center a few doors away. A couple of years later still he left WRL to become an SGI vice-president, where he is today.)

As a visiting associate professor, I found myself the ranking member of the project after Forest's departure. I ran the project on an informal basis, holding regular progress meetings while continuing to work on kernel andgraphics software. Midway through my sabbatical I was offered a full professorship by Stanford, which I initially declined as inappropriate for someone on sabbatical. I reversed my position when MIT, citing my thin PhD supervision, declined to match Stanford's offer with the corresponding promotion.

The Sun terminal was intended to consist of three Multibus boards in an 8"x10"x14" card cage, namely a CPU board for performing the actual computation, a graphics board controlling the monitor, and an ethernet board for connection to the embryonic Stanford network, then consisting of a 3 Mb ethernet. Prior to my arrival Andy had worked only on prototype graphics boards, while John Seamons had begun the design of an ethernet board. It was expected that someone would produce a Multibus board for the Motorola 68000 CPU imminently, so there were no plans to do this ourselves.

After Seamons left for Lucasfilm, Andy took on the ethernet design. In November 1979, having seen no sign of any manufacturer working on the expected CPU board, I suggested to Andy that he add this project to his load too. Andy felt the CPU board practically "designed itself" and hence was easy compared with the other two boards, which called for some innovations in order to be an adequate performance match to the CPU. The one question mark for the CPU board design was the memory management unit, to which Andy, Forest (who sent us a design while at PARC), and I all made significant contributions.

Andy spent the period January 1980 through July 1981 developing the three boards. My time was divided between teaching courses and working on kernel software, initially on Sunix and later helping John Seamons with a Unix port.

By August 1981 Andy had produced wirewrapped prototypes and printed-circuit-board artwork for all three boards. Through Jim Clark, Andy negotiated with CadLinc, a Detroit CAD (Computer Assisted/Aided Design) company, to manufacture Sun terminals under a non-exclusive license from Andy's company VLSI Systems Inc. (VSI), Stanford having declined this opportunity. Between that period and January 1982, VSI licensed the design to a total of eight companies, including Forward Technology, Bridge Communications, and Imagen.

At the same time Imagen was forming, under Les Earnest and Luis Trabb-Pardo, to manufacture printers based on the new Canon laser printer, which in turn was based on several years experience with laser+drum photocopying technology. Les and Luis found Andy's CPU board ideal for the Imagen printer. Luis wrote the first PROM monitor for the CPU board, subsequently rewritten by Jeff Mogul.

At about the same time we sent a prototype to John Seamons at Lucasfilm, who had been porting Version 5 Unix to the 68000. At this time I stopped work on Sunix in order to help John debug the Unix port.

In January 1982, Vinod Khosla, a recent Stanford MBA who had just left Daisy Systems, made a number of visits to our project, and eventually persuaded Andy to stop licensing the design and instead form a new company based on the Sun as its main product. Vinod persuaded his close friend Scott McNealy to join up. Plans for a company jelled in February, and Sun was officially founded at the end of February. Bill Joy came on board a month later following a visit to Berkeley in March by Andy, Vinod, Scott, and myself.

My involvement with Sun, the company, for its first year was as a consultant, during which time I designed the Sun logo, the Gallant font that one still sees today when booting a Sun workstation, the prom controller for the keyboard, and dithering software for Peter Costello's color graphics board. With John Gage I set up and took down Sun's first Siggraph booth in Boston in July 1982, and put together a suite of demos to maintain crowd interest. One evening Vinod, Andy, John, and I drove one of the Siggraph booth's Suns down to Brown University and demonstrated it to Andy van Dam's graphics group.

Later that year I started work on a C compiler for which I had some new ideas, but this proved a bigger project than I was able to squeeze into my limited consulting time and I scratched it after a quarter.

Starting April 1983, I took a two-year leave of absence from Stanford to work full time for Sun. In my first three months at Sun I designed and implemented Sun's Pixrect graphics interface, still used today as the software layer providing a uniform object-oriented interface between all Sun graphics boards and all programs writing either text or graphics to the monitor. After that I worked on developing a curve capability called Conix to be added to Pixrect, digital typography, and with Craig Taylor, on new windows algorithms. The first two of these yielded Siggraph papers, and Conix was subsequently incorporated into various graphics projects at Sun, but unfortunately never into Pixrect itself as I had intended. After returning to Stanford, I put the digital typography project on hold for two years, then put Gidi Avrahami to work on it for his PhD, which he recently completed, producing a very nice package for going all the way from ink artwork to an unhinted but otherwise nicely tuned Postscript font.

The above leaves out an awful lot. Hopefully some day I'll find the time to write at greater length on the early history of Sun. Meanwhile this will have to do.

Best,

Vaughan (Pratt), March 28, 1994